Key takeaways:

~ Sodium impacts blood pressure through the fluid balance regulation in the kidneys as well as through interacting directly with the lining of your blood vessels.

~ Salt sensitivity of blood pressure varies across populations, with higher prevalence in some groups (e.g., 62% in sub-Saharan Africans).

~ Genetic variations significantly influence individual salt sensitivity, with certain genotypes making people more prone to high blood pressure in response to high salt intake.

~ Understanding your genetic predisposition can help you either tailor your diet to decrease high blood pressure, if you are salt sensitive, or find alternate ways to decrease your high blood pressure.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

High blood pressure and salt:

Salt sensitivity in blood pressure refers to the phenomenon in which a person’s blood pressure rises in response to an increased intake of dietary salt (sodium). Salt is a combination of sodium and chloride, but the sodium molecule is more important in regulating blood pressure.

Both sodium and the amount of water in your bloodstream are integral to your blood pressure. If there is more fluid in your bloodstream (i.e. more water), your blood pressure will rise. The general rule is “water follows salt,” which means that an influx of sodium causes an increase in the amount of water retained by the kidneys, which then increases blood volume and blood pressure.

How much salt is too much? The WHO defines excessive sodium intake as more than 5 grams of sodium per day, and the FDA recommends less than 2.3 grams of sodium per day. Salt contains about 40% sodium, so 5 grams of sodium is about 13 grams of salt, and 2.3 grams of sodium is about 6 grams of salt.[ref][ref]

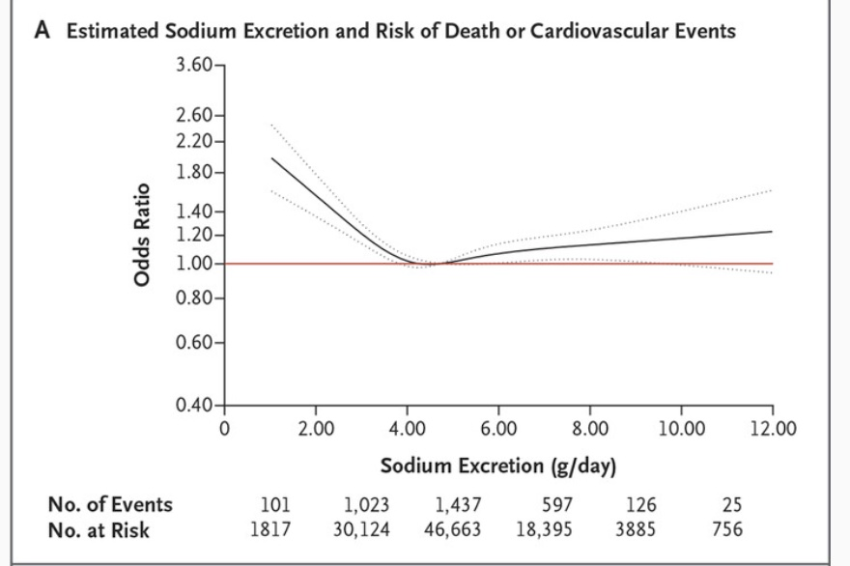

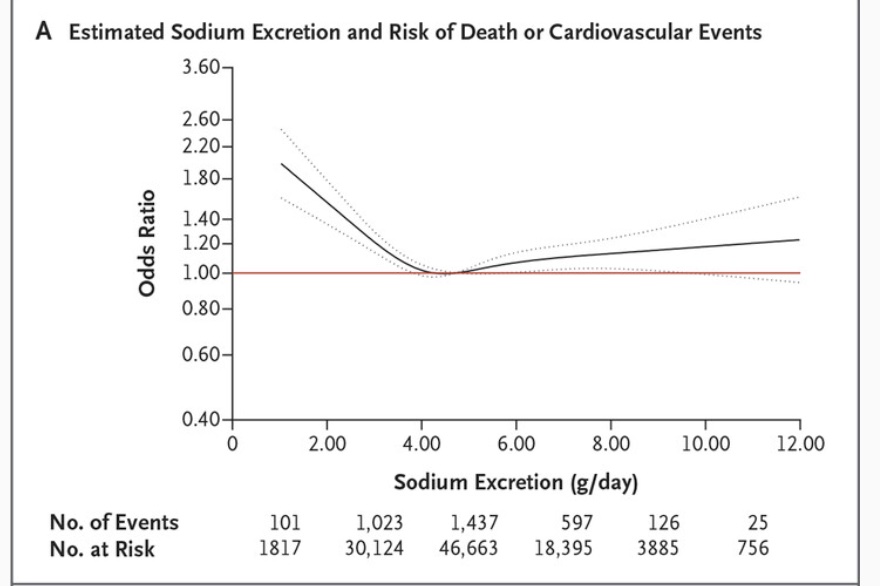

While it used to be advised to decrease sodium as much as possible, research now shows that both high and very low sodium intake levels are linked to increased mortality rates — a J- shaped curve.

One meta-analysis found that sodium intake between 3 to 6 g/day was associated with lower cardiovascular events and lower mortality risk.[ref] Another study involving over 100,000 patients found that the lowest mortality and lowest cardiovascular risk was associated with 3-5 g/day of sodium intake.[ref] Currently, the US RDA for sodium is 2.3 g per day, and the average consumption in the US is 3.4 g/day.[ref]

Here’s the overall sodium vs mortality curve of a NEJM study with 100,000 people (keep in mind that your individual need for salt may be different than the average).[ref]

Let’s dive into the regulation of blood pressure and how sodium from salt plays a role. Then we will look at how genetic variants in related genes affect salt sensitivity in blood pressure.

Sodium’s role in blood pressure regulation:

There are at least three ways that sodium is involved in blood pressure, with the RAAS system being primary.

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS):

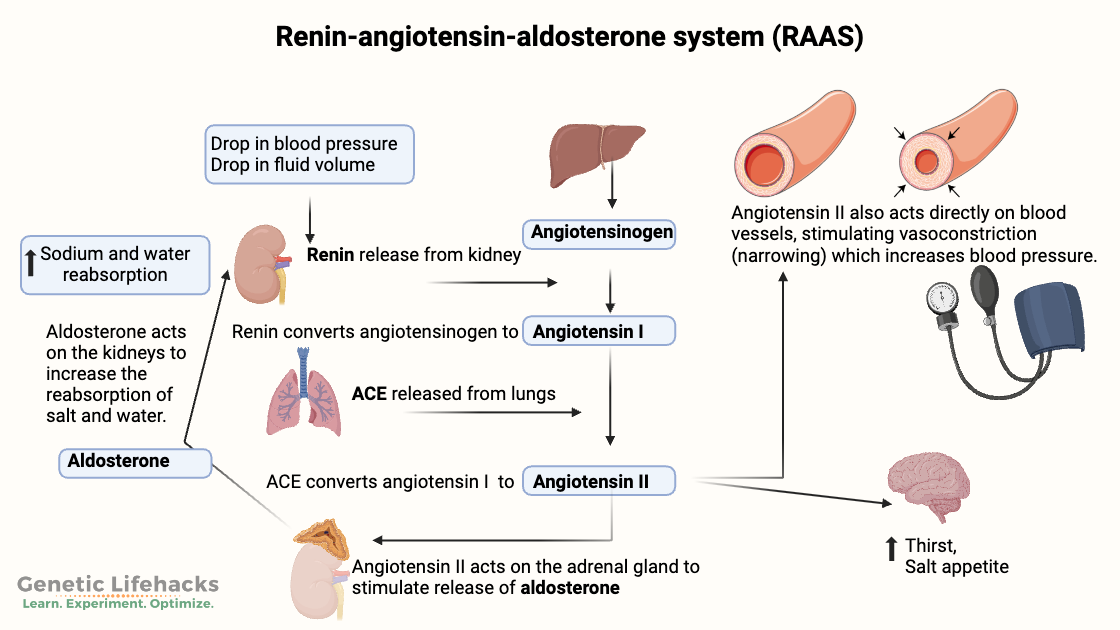

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) regulates blood pressure by balancing fluid and electrolyte levels. It also regulates blood vessel constriction. The RAAS system does this by regulating sodium and water absorption in the kidneys, which then impacts blood volume and systemic blood pressure.[ref]

Here’s how the RAAS system works:

- Renin is produced in the kidneys and is the rate-limiting step in the RAAS system.

- Angiotensin I is formed when renin interacts with a precursor, angiotensinogen, which is produced in the liver.

- ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme), located primarily in the lungs, converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II.

- Angiotensin II then acts on receptors in blood vessels to increase vasoconstriction and it acts on receptors in the adrenal glands to cause aldosterone to be released.

- Aldosterone then acts on the kidneys to increase sodium retention and reabsorption of water. [ref]

Renin is released when your sodium levels are too low or your blood pressure drops. This then causes more angiotensin II and blood vessel constriction to increase blood pressure. When salt intake is high, renin release is inhibited, leading to a reduced formation of angiotensin II and aldosterone. [ref]

Here’s an image to make this more understandable:

Endothelial glycocalyx:

Beyond the RAAS system, high sodium levels over the long term can also damage blood vessels leading to vascular dysfunction and high blood pressure.

Blood vessels are lined with a negatively charged layer of glycoproteins and proteoglycans called the glycocalyx. The glycocalyx acts as a barrier that maintains the selective permeability of the lining of the blood vessels. High sodium levels interact with the negatively charged glycocalyx and can damage it. When the glycocalyx is damaged by excess sodium, the damage then allows more sodium into the vascular endothelium which could increase blood pressure. In addition, damage to the glycocalyx impairs the production of nitric oxide there, further increasing blood pressure.[ref][ref]

Sympathetic nervous system activation:

The sympathetic nervous system controls heart rate, and sodium interacts with the nervous system in several ways. A high salt diet also increases the release of neurotransmitters in the sympathetic nervous system. This may also cause an interaction between angiotensin II and the baroreflex, which regulates heart rate. A long-term low-salt diet has the opposite effect. A long-term very low salt diet has been shown to paradoxically increase blood pressure by resetting the sensitivity of the baroreflex.[ref][ref]

Aldosterone is the hormone released by the adrenal glands to control sodium retention in the kidneys, and it does this through binding to mineralocorticoid receptors (MR). Additionally, there are mineralocorticoid receptors in the smooth muscle around blood vessels that cause constriction of the blood vessels (and increased blood pressure) when activated.[ref][ref]

Does a high sodium intake raise blood pressure for everyone?

While the most common advice for lowering blood pressure is to cut out salt, it turns out that reducing dietary sodium may not lower blood pressure for everyone.

The RAAS system is complex, involving kidney function, water balance (blood volume), sodium levels, angiotensin receptors, blood pressure, lung function, adrenal function, and stimulation via the sympathetic nervous system.[ref] It’s a balance that involves a lot of different mechanisms, and sodium is one part of it.

Adding to the complexity of the RAAS, the effect of high sodium on the glycocalyx and blood vessel health is also a link between sodium and blood pressure in some people.[ref]

Why is it important to understand whether you are likely to have salt-sensitive blood pressure?

Scenario: You go for a checkup and find that your blood pressure is high. Your doctor tells you to cut down on salt and come back in six monthsto see if your blood pressure goes down. If it doesn’t work, you move on to other treatment options, but you’ve already wasted six months. Research shows that salt reduction works for 25-62% of the population, depending on ancestry. If you know from your genetic data that a low-salt diet is likely to work for you, then it is a great first step in reducing high blood pressure. However, if it is unlikely to work for you, you may want to try other alternatives rather than wait and see.

Ancestry groups and salt sensitivity:

The genetic variants associated with salt sensitivity are more common in some populations than in others.

A large study in rural northern China (Han Chinese) found that about one-third of the adults were sodium sensitive, with blood pressure increasing due to more salt in their diet. In the study (called GenSalt), the low sodium diet included 3 g of salt per day for 7 days and the high salt diet included 18 g of salt per day for 7 days.[ref] Of note here is that their low sodium diet contained slightly more than the US recommended sodium intake…

A study in sub-Saharan Africa found that 62% of healthy adults with normal blood pressure had an increase in blood pressure in response to salt.[ref]

A 2015 review that included data from multiple studies found that salt sensitivity for blood pressure is “estimated to be present in 51% of the hypertensive and 26% of the normotensive populations”.[ref] Another study found that about 25% of people with mild hypertension had their blood pressure increase a little bit on a low-sodium diet. [ref]

Everyone is unique and even knowing the odds of salt-sensitive blood pressure based on your ancestry isn’t enough to predict your individual response. To get a better view of your response, check out the genetic variants below that are related to salt sensitivity.

Genotype report: Salt Sensitive Blood Pressure

Member Content:

Not a member?

Join today.

♦ Access to full articles, including Genotype and Lifehacks sections.

♦ See your genetic data integrated into articles and reports.

Join Here

Lifehacks:

As you can see, there are quite a few genes that play a role in salt sensitivity and blood pressure. If you have several variants related to salt sensitivity, then reducing sodium may be effective for you in lowering blood pressure. The list above is not complete, although it hits on the more important SNPs, and research is still ongoing. So while you can’t use the genotype report to completely rule out salt sensitivity, it can give you a good idea if you should look at other reasons for high blood pressure.

Diet and Lifestyle:

Tracking:

Track your salt intake and your blood pressure for a period of time to see if there is a correlation. Cronometer.com is a free web app for tracking what you eat and seeing the amount of different nutrients, including sodium, consumed for the day.

Low-sodium, higher potassium diet:

If you want to reduce your sodium intake, start by cutting down on the foods highest in sodium. For the average diet, the following are the biggest sources of sodium:[ref]

| Common foods high in sodium (avoid on a low sodium diet) | |

|---|---|

|

|

Potassium helps to balance out your electrolytes and your sodium intake and can help to reduce blood pressure.[ref] Foods high in potassium include:[ref]

| Food | Potassium (mg per serving) |

Percent DV* |

|---|---|---|

| Apricots, dried, ½ cup | 755 | 16 |

| Lentils, cooked, 1 cup | 731 | 16 |

| Squash, acorn, mashed, 1 cup | 644 | 14 |

| Prunes, dried, ½ cup | 635 | 14 |

| Raisins, ½ cup | 618 | 13 |

| Potato, baked, flesh only, 1 medium | 610 | 13 |

| Kidney beans, canned, 1 cup | 607 | 13 |

Low-sodium salt substitutes may not be all that effective:

A Cochrane review of low sodium salt substitutes found that there was “little to no difference, on average, in hypertension”.[ref]

Exercise:

Many studies show that regular, moderate exercise is good for your heart and your blood pressure. How much? What kind? Well, the best exercise seems to be the one that you will actually do. So if you like to walk, go for a walk; if you like to play pickleball, then play regularly.[ref][ref][ref]

Quality Sleep:

Good sleep helps control blood pressure.[ref][ref][ref] Blocking blue light in the evenings has been shown to increase melatonin production by 50% and prevent sleep disorders.

Vitamins and natural supplements with clinical trials showing a significant reduction in blood pressure:

Member Content:

Not a member?

Join today.

♦ Access to full articles, including Genotype and Lifehacks sections.

♦ See your genetic data integrated into articles and reports.

Join Here

Related articles:

About the Author:

Debbie Moon is the founder of Genetic Lifehacks. Fascinated by the connections between genes, diet, and health, her goal is to help you understand how to apply genetics to your diet and lifestyle decisions. Debbie has a BS in engineering from Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in biological sciences from Clemson University. Debbie combines an engineering mindset with a biological systems approach to help you understand how genetic differences impact your optimal health.