A new preprint study looks at the genetic variants more commonly found in people with Long Covid. This is encouraging for many people struggling with long Covid symptoms, raising hopes that understanding the genetic susceptibility will lead to much-needed treatments.

Let’s look at how the study was done and what the results mean, and then in the genotype report section you can see your genotypes for the long Covid associated genes.

23andMe study on long Covid:

The goal of the study was to investigate the genetic factors associated with long Covid by conducting a genome-wide association study (GWAS) across different populations. The study authors also used Mendelian randomization to see if there are genetic links between long Covid and other chronic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), fibromyalgia, and depression.

Study Design:

The study involved data from 23andMe users (adults). It included 53,764 Long COVID cases and 120,688 controls — across different genetic ancestry groups. Since it is a 23andMe study that contains a lot of users who are related to each other, the analysis screened out closely related individuals so as not to skew the results.

The study participants answered survey questions about their diagnosis of Covid, and then the persistence of symptoms at least a month or longer after infection. Note that this is all self-reported and not necessarily diagnosed by a physician.

Having long Covid was defined by answers to the question: “Have you experienced post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (also called ‘Long COVID’ or ‘Long Haulers’)?”. The long Covid group was then further selected as people who answered that they had symptoms that impacted daily life “moderately, quite a bit, or extremely”.

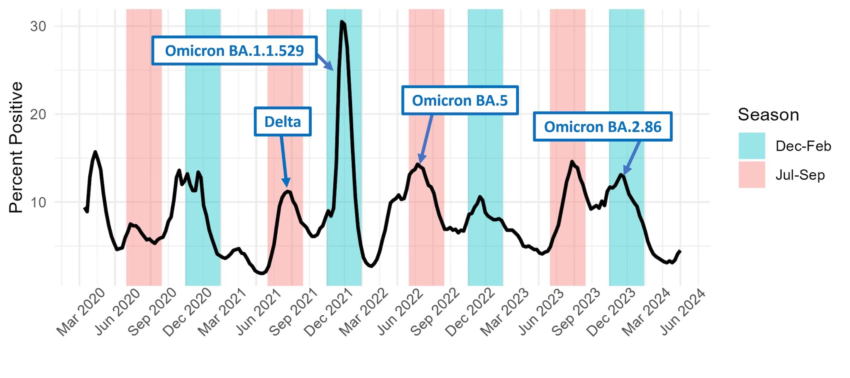

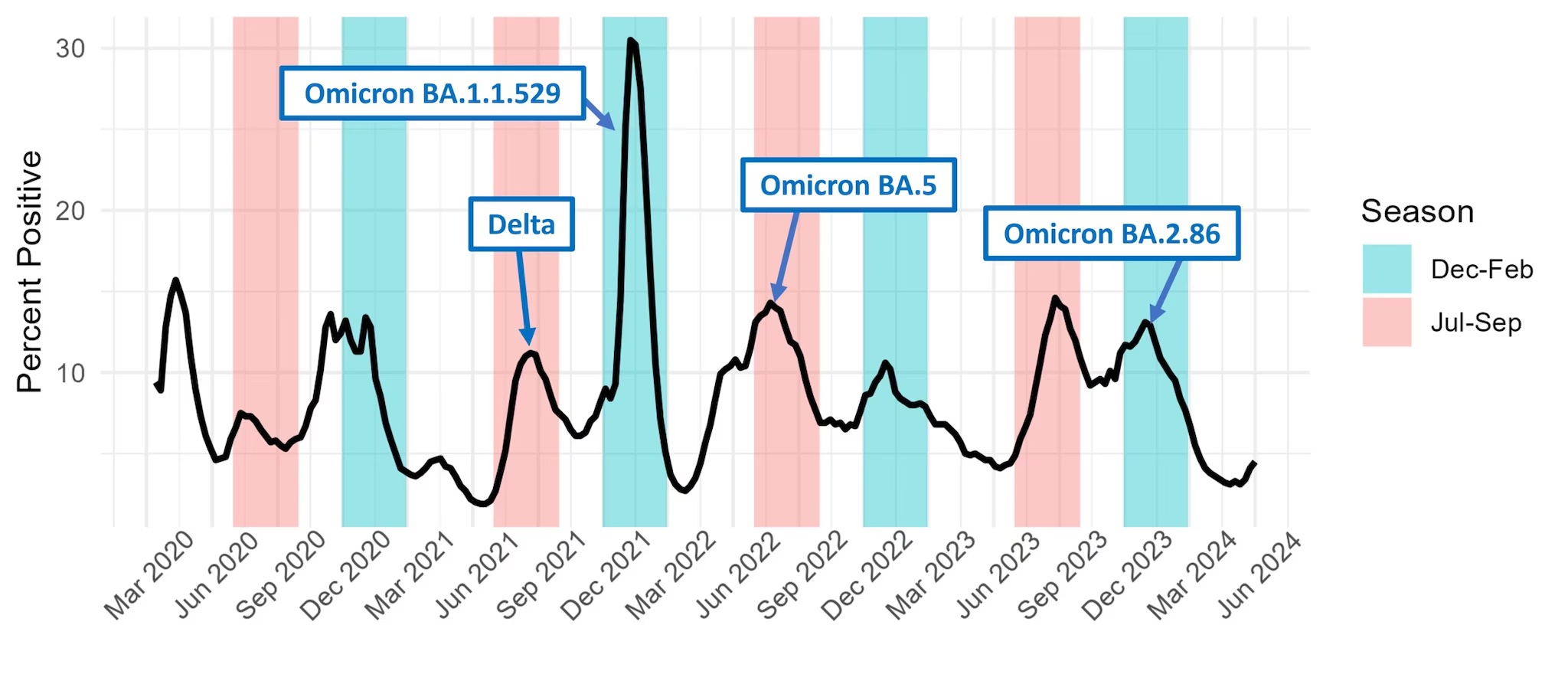

The survey data was collected between Aug. 2021 and Feb. 2024. This data then should cover people who had any of the different variants of SARS-CoV-2.

The researcher then used the 23andMe raw data (about 650,000 SNPs) and imputed a larger data set of about 110 million variants. Imputing genotypes means that they take what is known from the actual sequenced data and use statistics on how chunks of DNA are inherited to figure out what the rest of the SNPs are likely to be. This is usually done with 98% or higher accuracy. The researchers then also imputed likely HLA types.

Results of the GWAS:

The genome-wide association study results show which genetic variants are statistically related to the disease or trait being studied. This is an agnostic approach without a preconceived idea as to which genes are involved in the disease or trait.

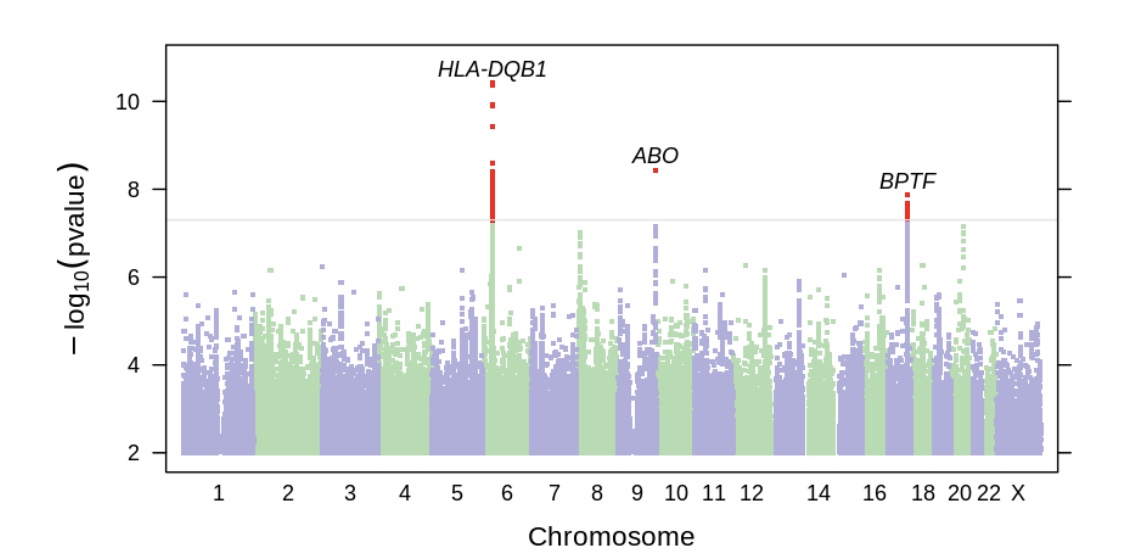

In this study, the GWAS results highlighted three different genetic regions.

The first was in the HLA genes on chromosome 6. The HLA genes are part of the immune system and help the body identify whether something is a normal part of the body (“self”) or a foreign invader, such as viruses or bacteria. There is a huge amount of variation in the HLA genes in the human population. It’s a survival advantage to the population as a whole to have a lot of diversity in the ability to recognize new viruses or pathogens. With lots of diversity, it’s likely that some individuals will have the ability to mount an effective defense against a new pathogen — and thus the whole population won’t be wiped out.

Thus, it is unsurprising that different HLA types increase or decrease the susceptibility to Covid and also the susceptibility to long Covid. The multitude of different HLA types are linked to either increased or decreased susceptibility to many different pathogens and also to how quickly and thoroughly someone clears a pathogen.

The top hit in the GWAS was rs9273363 (in the genotype report section below if you want to check your data) which increased the relative risk of long Covid by 6%.

Putting the risk into perspective: The study showed that the variant had an OR=1.06. This is a statistical measure – odds ratio – showing the increase or decreased odds of an event occurring. In this case, it shows that individuals with the variant have a 6% higher chance of developing long Covid than those without the variant. This is a 6% increase in the relative risk. Thus, if the odds of getting long Covid are 1 in 10 (making the numbers easy), having the GWAS identified variant increases your individual risk to 1.06 in 10. While the increase in risk is slight, and thus not really predictive for an individual, the GWAS hits are important because they show that the gene is likely important in susceptibility.

The second most significant gene identified in the study was the ABO gene, which is important for identifying blood type (type O, type A, type B, or type AB). The variant identified is linked to blood type O and decreased the relative risk of long Covid. Blood type O is also at an overall decreased risk of getting Covid, and people with type O blood may also be at a decreased risk of excess clotting.

Related article: Blood type and coronavirus susceptibility

The third area that showed up in the study as being statistically significant is in the area related to three genes BPTF, C17orf58, and KPAN2. This is common in GWAS studies to know that there is a signal (a SNP, in this case) that is linked to variants in multiple surrounding genes. For this study, in people with European ancestry, the top identified SNP is likely influencing C17orf58, a gene associated with heart attack risk, or KPAN2, which encodes a nuclear transport factor (moves proteins or RNA in or out of the cell nucleus). The KPAN2 gene is of particular interest here because it is associated with viral suppression and has been shown to interact with the SARS-CoV2 genome. The BPTF gene is involved in chromatin remodeling – affecting gene transcription in the nucleus.

Overlap with other conditions:

The researchers also looked at whether genetic variants linked to other diseases overlapped with people with long Covid. Using Mendelian randomization, they found that there was strong evidence of causal overlap with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and lupus. (See Figure 3 in the study).

Genotype report:

HLA-DQB1 locus:

Check your genetic data for rs9273363 (23andMe v4; v5)

- A/A: no increase in risk of long Covid

- A/C: slight increase in the relative risk of long Covid (OR=1.06)

- C/C: slight increase in the relative risk of long Covid (most common genotype, OR=1.06)

Members: Your genotype for rs8176719 is —.

ABO gene: determines your ABO blood type

Check your genetic data for rs8176719 (23andMe v4; v5)

- D/D: likely to be blood type O[ref] a little less likely to have long Covid (also less susceptible to getting Covid)[ref]

- D/I: likely to be type A or type B

- I/I: likely to be type A, type B, or type AB

Members: Your genotype for rs8176719 is —.

BPTF gene:

The variant identified in the region of the BPTF gene, rs2080090, isn’t found in 23andMe v4 or v5 data. The variant slightly reduced the relative risk of long Covid.

Conclusion:

This was the largest GWAS study by far on long Covid. While the use of survey questions and self-reported diagnosis is less robust than clinical diagnoses, the large number and diversity of participants in the study is a big plus.

However, this type of study can’t really be used for an individual to know whether they are likely to get long Covid. The genes identified are interesting in their connection to susceptibility to Covid and immune response. But they don’t give much direction about how to prevent or treat long Covid.

The Mendelian randomization analysis of how long Covid likely overlaps with chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia is interesting to see. There was a fairly strong signal there that some of the same pathways are involved. The researchers also looked at other chronic conditions, and they didn’t find much of a genetic correlation with clotting, DVT, heart attacks, or asthma, which is also important to know.

Screenshot

About the Author:

Debbie Moon is the founder of Genetic Lifehacks. Fascinated by the connections between genes, diet, and health, her goal is to help you understand how to apply genetics to your diet and lifestyle decisions. Debbie has a BS in engineering from Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in biological sciences from Clemson University. Debbie combines an engineering mindset with a biological systems approach to help you understand how genetic differences impact your optimal health.